When my lymphoma relapsed, the plan was to try a stem cell transplant. For the transplant to work, I had to be in remission. So, I had 2 cycles of R-GDP chemo, followed by a PET scan. The PET scan showed a mixed response. Much of the lymphoma had disappeared but one node in my chest had grown. Unfortunately, this meant the chance of the stem cell transplant curing the lymphoma had dropped to around 20%. Rather than continue with the transplant, we decided to try for a new type of immunotherapy, CAR-T therapy.

CAR-T therapy is a revolutionary new cancer treatment that involves genetically modifying a person’s own immune system to fight cancer. Most other treatments only work while you’re having them, but CAR-T is a living treatment. So, it stays in your body fighting the lymphoma. Amazing! But it’s not without its issues.

CAR-T therapy is complex, very very expensive, and risky. Around 5% of patients die from the treatment and 25% end up in intensive care. The cost per patient is over £280k and there are only a few labs that can manufacture the CAR-T cells. So, the NHS only make it available to lymphoma patients who’ve had 2 previous failed lines of treatment. Hospitals can’t make the decision to give CAR-T themselves, a national panel meets weekly to consider potential cases. This meant a short but agonising wait to hear whether or not I would be given the treatment. Thankfully, I was and preparations for the treatment started straight away.

CAR-T is a very demanding treatment, and I had to be fit enough to have it. This meant a lot of tests! In the weeks leading up to treatment I had an ECG, echocardiogram, pulmonary function test, chest X-ray, PET scan, 24-hour urine analysis, physical examination and lots of blood tests and swabs.

The treatment is based around T cells. These are the part of the immune system that patrol the body looking for and destroying cells that have been damaged or infected. However, cancer is good at evading this natural defence mechanism and so the T cells aren’t able to recognise the cancerous lymphoma cells. CAR-T therapy works by inserting some extra instructions into the DNA of the T cells, which enables them to spot and then destroy cancerous B cells.

Unfortunately, it’s not yet possible for CAR-T cells to distinguish between healthy and cancerous B cells, so the treatment kills all of the B cells. This isn’t too much of a problem for lymphoma, as it’s possible to live just fine without B cells and drugs can be used to plug the gaps left in the immune system. However, it means CAR-T can currently only be used for a small number of mostly blood cancers. 1BBC News – ‘Living drug’ offers hope to terminal blood cancer patients.

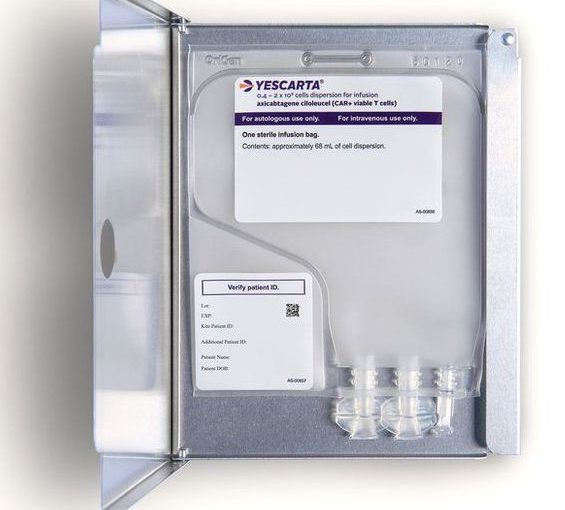

The treatment works by first extracting a patient’s T cells. These are then sent to a lab (in my case they were flown to America) where they are genetically modified before being given back. I was offered a choice between two different types of CAR-T. I opted for Yescarta, which has more intense side effects and slightly higher risk of death but also has a slightly higher chance of achieving a lasting remission. In studies, about 40% of CAR-T cell patients go on to achieve lasting remission.

Collecting the cells happens through a process called aphesis and it was painless. Blood was taken out through a central line that I’d had inserted a couple of weeks earlier. The aphesis machine then separated out the T cells and pumped the rest of the blood back in. It took around 5 hours to collect enough of my cells.

Once the cells arrived back, the treatment could start.

References

- 1BBC News – ‘Living drug’ offers hope to terminal blood cancer patients