In my previous post, I talked about what CAR-T therapy is and the process of preparing to have it. In this post, I explain the actual procedure I went through.

Having been extracted and flown over to America, my genetically modified T cells arrived back in the UK three weeks later. It was now time to prepare my immune system to receive them back. This meant yet more chemo! The purpose of this lymphodepleting chemo was to kill off my existing T cells and make space for my new supercharged ones. The chemo took three days and was given on the haematology day unit. I had no major side effects other than a lot of fatigue. I then had a rest day before being admitted to the haematology ward the next day. Nothing happened on the day of admission, it was just settling into the room and a few blood tests. Then the real CAR-T therapy fun started:

Day 1 (Monday)

At 8am, I was taken for an MRI brain scan. This was just to be used a reference in case I later developed any neurological side effects which are common with CAR-T.

At 8am, I was taken for an MRI brain scan. This was just to be used a reference in case I later developed any neurological side effects which are common with CAR-T.

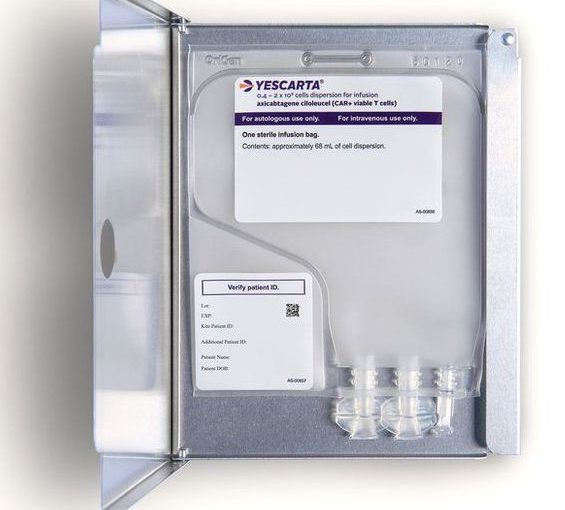

At about 11am, the T-cells arrived in the room accompanied by some folks from the hospital’s stem cell lab, who supervised their administration.

The CAR-T cells were given back to me via my central line. There was a slight taste of chemicals as they went in but there were no other side effects. The infusion was very small and only took about 15 minutes. It was all a bit anticlimactic given everything that had gone on in the weeks prior.

The nurse monitored me every 15 minutes for a couple of hours, but I had no reactions so this was reduced to every 4 hours. As well as the standard blood pressure and temperature observations, I had to have regular neurological assessments. These involved answering a set of standard questions, counting backward from 100 in tens, and writing out a standard sentence. These were repeated every 4 hours for the next 30 days.

Day 2 (Tuesday)

Day 2 was very uneventful. The assessments continued but I had no reactions or side effects. So far, so boring. I wasn’t allowed to leave the room but thankfully, I’d brought a portable projector and a VR headset to keep me entertained.

Day 3 (Wednesday)

I woke up with sore throat but I was otherwise ok and my blood results were not concerning. My temperature crept up during the day and I started to feel more lethargic and malaise. By 6pm, my temperature had reached 38oC, which was caused by Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS).

CRS is a side effect that affects most CAR-T therapy patients. It’s caused by the modified T cells releasing a chemical messenger (cytokines) that signal other cells to multiply. It is graded 1 to 4, with 4 being the most serious and requiring intensive care. It often resembles a serious infection with temperatures, shivers, aches etc. However, it can also cause neurological symptoms, including confusion, seizures and loss of consciousness.

The hospital follows a strict protocol for CAR-T therapy. My temperature of 38oC was considered grade 1 CRS, so I was examined by the doctor and treated with IV antibiotics and IV Paracetamol. Blood cultures were taken from my arm and from my line (these were all negative). I also had a chest X-ray, which was clear.

Day 4 (Thursday)

My temperature was slightly elevated in the evening (37.5oC) and I was given oral Paracetamol. The IV antibiotics continued. I began feeling more and more lethargic and malaise.

Day 5 (Friday)

I continued feeling lethargic and malaise with a slightly elevated temperature of 37.8oC in the evening, and I also developed mild diarrhoea. The oral Paracetamol and IV antibiotics continued and the blood cultures were repeated (and again were negative).

Day 6 (Saturday)

My temperature was still elevated and I was still feeling very tired and poorly. I slept most of the day. I developed a bit of a cough but a chest examination was clear. The oral Paracetamol and IV antibiotics continued.

Day 7 (Sunday)

My temperature was still spiking and I was still very sleepy and didn’t feel like getting out of bed at all. Oral paracetamol and IV antibiotics continued and the blood cultures repeated.

Day 8 (Monday)

Again I was very tired and sleepy and I now had a thumping headache whenever I moved. My temperature rose above 38.5oC, which was the trigger for stage 2 CRS. At stage 2, the protocol dictated that I was given Tocilizumab, a drug that dampens down the immune system, reducing the effects of the CRS. It didn’t immediately improve my symptoms, so I continued on IV paracetamol and antibiotics.

I had another chest X-ray which was again clear.

Day 9 (Tuesday)

By now the Tocilizumab was kicking in and I was starting to feel a bit better and have more energy. My temperature reduced to 37.4oC. I continued on the IV antibiotics.

Day 10 (Wednesday)

I was feeling pretty much back to normal and had no temperature spikes during the day. A mild temperature spike in the evening 37.5oC was treated with oral Paracetamol and the blood cultures were repeated. I continued on the IV antibiotics.

Day 11 (Thursday)

I was feeling more energetic and had no temperature spikes. The antibiotics were stopped and I was monitored for 24 hours.

Day 12 (Friday)

I was feeling ok and the doctors were happy to discharge me. My partner had to continue doing temperature and neurological assessments three times a day. The CAR-T specialist nurses phoned me every day to check on me, and I visited the outpatient department weekly to see the doc and have my line dressing changed.

I’m now on day 21 and continue to be fine. The next major milestones will be the 1-month and 3-month PET scans, which will show whether or not the CAR-T cells are working. The doctors have explained that it’s normal to still see some disease on the 1-month scan, but if the treatment is working, there shouldn’t be any progression 🤞